What Is The Most Congressional Districts Can Differ In Size

Equal population

The U.S. Constitution requires that each district have about the aforementioned population: each federal commune within a country must have about the same number of people, each land commune inside a land must accept about the same number of people, and each local district inside its jurisdiction must have about the same number of people.

- Congressional districts. The standard for congressional districts allows relatively small deviations, when deployed in the service of legitimate objectives. States must make a good-organized religion effort to describe districts with the same number of people in each district inside the country, and whatever district with more or fewer people than the boilerplate must exist justified by a consequent land policy. Merely consistent policies that leave a relatively small spread from largest to smallest district will probable be constitutional. In 2012, for example, the Supreme Court approved a congressional plan in West Virginia with 0.79% population variation based on keeping canton lines intact.

These population counts are calculated based on the total number of people in each state, including children, noncitizens, and others not eligible to vote. After the Civil State of war, we amended the Constitution to ensure that each and every individual nowadays in the country would be represented in federal districts. On July 21, 2020, President Trump purported to advise that he had the authority to exclude undocumented individuals from the demography count — if valid, that would accept afflicted not only how many districts us got, but how those districts were divided within a state. Litigation over the effect hitting procedural hurdles as it was unclear whether the information would be ready in time for President Trump to brand the determination he'd flagged; ultimately, the data were delayed long enough for the Biden Administration to contrary course. Equally in prior decades, the Census counts will include everyone for purposes of apportionment.

- State and local legislative districts have a bit more flexibility on the numbers; they have to exist "essentially" equal. Over a serial of cases, information technology has go accustomed that a programme volition be constitutionally suspect if the largest and smallest districts are more than 10 percentage apart. This is non a hard line: a land plan may be upheld if there is a compelling reason for a larger disparity, and a state plan may be struck downwards if a smaller disparity is not justified by a good reason.

Some states concur their country districts to stricter population equality limits than the federal constitution requires. Colorado, for case, allows at most five percent total divergence between the largest and smallest districts; Missouri asks districts to be no more than than one percent in a higher place or below the average, except that deviations of upwards to iii per centum are permitted to maintain political boundaries. Iowa both limits the total population deviation to v percentage, and besides sets the overall average deviation at no more than one percent.

As far equallywho is counted for purpose of equalizing state and local districts, the Supreme Courtroom has been less definitive virtually what the Constitution requires. In 2011, each and every state counted the total population. But some have suggested other measures, including voting-age population ("VAP"), denizen voting-age population ("CVAP"), or registered voters. Each of these alternatives depends on a logic of exclusion, denying representation to those who pay taxes and who are expected to live by our laws. Though the Supreme Court has formally left this question for a future example, their last word in the area left serious question as to whether such measures would be constitutional.

Minority representation

The other set of major federal redistricting rules concerns race and ethnicity. The extent to which redistricting can or must account for race and ethnicity is sometimes seen equally a particularly thorny problem, simply that's in office because some people have a vested involvement in making it seem hard. Race relations and electoral politics are both quite complicated. But the police force on race and ethnicity in the redistricting context essentially boils downwards to iii concepts. And while there are without question some complications in the details — including some hurdles for challengers trying to challenge maps in court — the overview for those drawing the lines is pretty straightforward.

- Don't depict lines that set out to harm voters based on their race or ethnicity.

- Where bigotry plays or has played a significant part, and where voting is substantially polarized along racial or ethnic lines, wait at electoral patterns and decide whether minorities already have proportionate electoral power. If non, the Voting Rights Deed might require a change to the lines to give a meaty and sizable minority community equitable electoral opportunity they practise not currently enjoy.

- When considering race in drawing districts, whether to satisfy the Voting Rights Act or otherwise, consider other factors in the mix as well.

- Intentional discrimination. For more than than 100 years, the Constitution has prohibited intentional regime efforts to treat similarly situated people worse than others, because of their race or ethnicity. In redistricting, one ploy is called "smashing": splintering minority populations into pocket-size pieces across several districts, then that a big grouping ends up with a very little chance to impact whatsoever single ballot. Some other tactic is called "packing": pushing as many minority voters every bit possible into a few super-concentrated districts, and draining the population's voting ability from anywhere else. Other tactics abound. And they accept been used with disappointing frequency.Redistricting legislation usually just describes which census blocks fall in which districts, or which streets district lines follow: nada in a redistricting statute looks like it has annihilation to do with race. Merely if the line-drawers intentionally drew the lines to damage residents specifically because of their race, that's almost always illegal.

That remains true no matter the underlying motive for the discrimination. Sometimes, the reason for intentional bigotry is old-fashioned hatred or stereotype. But singling out racial minorities for worse treatment considering of the candidates or parties they prefer still involves singling out racial minorities for worse treatment. And it nevertheless invites peculiarly close scrutiny under the constitution.

- Voting Rights Human activity. The federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 was designed to combat tactics denying minorities the correct to an effective vote, including redistricting techniques like those higher up. Equally federal police, the Voting Rights Act overrides inconsistent state laws, just like the ramble equal population rule overrides other state laws.From 1965-2013, the Voting Rights Human action had an specially powerful provision targeting the jurisdictions with the worst history of discrimination. In these areas, the Voting Rights Human action required every change in election rules to be run by the Department of Justice or a federal court before they took effect, stopping discrimination before information technology had the chance to piece of work. In 2006, Congress last revisited the function of the statute designating which jurisdictions should be covered. Simply in 2013, the Supreme Courtroom decided in Shelby County five. Holder that this 2006 renewal was non sufficiently tied to electric current conditions; their decision striking down the coerage provision essentially left no jurisdictions covered. In 2019, the House of Representatives passed a new coverage provision, but information technology did not go along through the Senate.Later on Shelby County, the most powerful remaining provision of the Voting Rights Act is Section 2 of the Act, which blocks commune lines that deny minority voters an equal opportunity "to participate in the political procedure and to elect representatives of their choice." It applies whether the deprival is intentional, or an unintended cease upshot. Courts essentially test whether the way that districts are fatigued takes decisive political power away from a cohesive minority bloc otherwise at risk for discrimination.

There are iii threshold conditions for a court finding that districts need to exist redrawn because section ii has been violated. (These are oftentimes called Gingles conditions, after the Supreme court'due southThornburg v. Gingles case.)

The outset asks whether it is possible to draw a district so that a bulk of voters belong to a geographically "compact" racial, ethnic, or language minority community. Compactness has never been precisely defined in this context, but generally refers to populations that are not peculiarly "far-flung," and where the boundaries are fairly regular, without extensive tendrils. This firstGingles condition basically tests whether a sufficiently large minority population is geographically distributed and so that they could control a reasonable commune.

The secondGingles status tests whether the minority population normally votes as a bloc, for the aforementioned type of candidate. This is a nuanced test: not whether the community usually votes for Democrats or Republicans (or others), but whether they would, given a off-white mix of candidates, vote for the aforementionedtype of Democrats or Republicans (or others).

The thirdGingles status tests the potential competition: whether the residue of the population in the area ordinarily votes as a bloc for different candidates than those preferred by the minority community. If and then, this would mean that the minority's preferred candidate would almost always lose — if the minority customs'due south voting power were not specifically protected. Together, the second and third conditions are known generally as "racially polarized" voting.

If the iii threshold conditions to a higher place take been met, courts and so await to the "totality of the circumstances" to determine whether the minority vote has been diluted, drawing from the U.South. Senate's legislative study when the Voting Rights Deed was passed. Most of these circumstances chronicle to the extent of historical or contextual discrimination. 1 factor that has been singled out every bit peculiarly important is rough proportionality: whether minorities have the opportunity to elect representatives of their choice in a number of districts roughly proportional to the percentage of minority voters in the population equally a whole. Section 2 does not guarantee proportionality. Just if a minority grouping with 20% of a state's eligible population could already elect representatives in xx% of the state's districts, courts volition be more hesitant to notice a violation of section two even if the iiiGingles weather are met. And if the minority group does not take such an opportunity, courts will often be more decumbent to find a violation.Courts accept largely articulated Section 2's meaning after plans accept been fatigued and challenged, and so the tests above are framed retroactively. For those drawing the lines and seeking to avoid legal trouble, the usual technique involves protecting substantial minority populations in racially polarized areas, by drawing district lines so that those minorities have the functional opportunity to elect a representative of their pick.

- Considering other factors. The Supreme Court has also said that the Constitution requires it to wait skeptically at redistricting plans when race or ethnicity is the "predominant" reason for putting a significant number of people in or out of a district. This does not mean that race tin can't be considered, or that when districts fatigued primarily based on race are invalid. Information technology means that there has to be a actually good reason for subordinating all other districting considerations to race. (And the Court has also repeatedly implied that one such compelling reason is compliance with the federal Voting Rights Deed.)In practice, this ways that those drawing the lines try non to let racial considerations "predominate," past considering other factors at the same time. This is not terribly difficult; there are lots of other considerations that become into deciding where to draw a particular district line, similar the residential clustering of groups of voters with common interests, or the locations of municipal boundaries or concrete geographic features, or the want to keep a district relatively close together.It may be useful to think of this rule similar most of us call up about driving a automobile. It'south important to keep to the speed limit. If you obsess over your speed, and stare only at the speedometer, subordinating every other stimulus, you're likely to crash. But if you pay attending to the road, and surrounding traffic, and the directions to your destination, and signaling when yous change lanes, and the car temperature, and the amount of gas you've got left, and the weather, and the music on the radio — and likewise cheque in on your speed from time to time — then your attention to the speed doesn't "predominate."

Contiguity

Contiguity is the most common rule imposed past united states: by land constitution or statute, 45 states require at least one chamber'southward state legislative districts to be contiguous. 18 states have similarly alleged that their congressional districts volition be contiguous. (The smaller number reflects the fact that few states have whatsoever express legal constraints on congressional districting. In practice, the vast majority of congressional districts — perhaps every ane in the 2020 wheel — will be drawn to exist contiguous.)

A district is contiguous if yous tin can travel from whatsoever betoken in the district to whatsoever other point in the district without crossing the commune'due south purlieus. Put differently, all portions of the district are physically adjacent. Well-nigh states require portions of a district to be connected by more than than a single point, but don't further require that a district be connected by territory of a certain area.

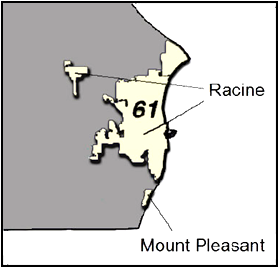

Few redistricting concepts are absolute, and contiguity is no exception. Many states crave contiguity only "to the extent possible," and courts generally have anomalies that otherwise seem reasonable in context. For case, the metropolis of Racine, Wisconsin, has a non-contiguous purlieus (boundaries like this are fairly common by-products of annexation). And so, in 2001, the legislature drew Wisconsin'southward 61st state assembly district to incorporate most of the city of Racine — with a noncontiguous portion of the commune embracing the noncontiguous portion of the city. In 2011, Wisconsin's 47th state assembly district did much the same for the noncontiguous portions of Blooming Grove and several other noncontiguous wards, and the 60th state assembly district did the same for the noncontiguous portions of Cedarburg.

H2o also gets special treatment for contiguity. In most cases, districts divided by water are face-to-face if a common means of transport (like a span or ferry route) connects the ii sides of the district. Island districts are mostly contiguous as long as the island is part of the same district every bit the mainland area closest to the island or most tied to the isle by these sorts of transport routes. In Hawaii, where at that place is no mainland to consider, the land constitution prohibits the drawing of "canoe districts" — districts that are spread across more than one major island group, where it is necessary to use a "canoe" to travel betwixt unlike parts of the district.

Political boundaries

The next most common state rule is a requirement to follow political boundaries, like county, city, town, or ward lines, when cartoon districts. By state constitution or statute, 34 states crave state legislative districts to show some bookkeeping for political boundaries; 15 states impose similar constraints on congressional districts. Most often, country law concerning political boundaries leaves a fair amount of flexibility in the mandate — one common teaching is to continue to political boundaries "to the extent practicable." And like all other state redistricting law, this rule must bend where necessary to federal equal population or Voting Rights Act constraints.

It is worth remembering that some cities or towns spill over county lines; fifty-fifty though counties are commonly bigger than cities, keeping strictly to county lines may hateful cut off pieces of these "spillover" cities or metropolitan areas.

Also, if counties or cities have to exist split to comply with other redistricting requirements, most state law does not specify whether it is better to minimize the number of jurisdictions that are carve up, or to minimize the number of times that a given jurisdiction is separate. The former might hateful splitting a few jurisdictions into many pieces; the latter might mean splitting a greater number of jurisdictions, but into fewer pieces. (As an exception to the general flexibility, Ohio has a rather detailed set of constraints describing how counties and other municipalities are to be divide if they take to be split at all.)

Compactness

About equally often as state law asks districts to follow political boundaries, it asks that districts exist "compact." By constitution or statute, 32 states require their legislative districts to be reasonably compact; 17 states require congressional districts to be compact as well.

Few states define precisely what "compactness" means, just a district in which people mostly alive near each other is usually more compact than one in which they do non. Almost observers look to measures of a district'southward geometric shape. In California, districts are compact when they do not bypass nearby population for people farther away. In the Voting Rights Human action context, the Supreme Court seems to have construed compactness to signal that residents take some sort of cultural cohesion in common.

Scholars have proposed more than thirty measures of firmness, each of which can exist applied in different ways to individual districts or to a plan as a whole. These mostly fit into three categories. In the showtime category,contorted boundaries are most important: a commune with smoother boundaries will be more than compact, and one with more than squiggly boundaries volition be less compact. In the second category, the degree to which the commune spreads from a key core (called "dispersion") is most important: a district with few pieces sticking out from the center volition be more compact, and one with pieces sticking out farther from the district'due south center volition be less compact. In the 3rd category, the relationship ofhousing patterns to the district'due south boundaries is about important: commune tendrils, for example, are less meaningful in sparsely populated areas but more meaningful where the population is densely packed.

In practice, compactness tends to exist in the eye of the beholder. Idaho, for instance, says that its redistricting commission "should avoid cartoon districts that are oddly shaped" — which is more specific than well-nigh states. But 7 states appear to specify a particular measure of compactness: Arizona and Colorado focus on contorted boundaries; California, Michigan, Missouri, and Montana focus on dispersion, though in dissimilar ways; and Iowa embraces both.

Communities of interest

Preserving "communities of interest" is another common criterion reflected in state law. By constitution or statute, xv states consider keeping "communities of interest" whole when cartoon state legislative districts; xi states exercise the same for congressional districts.

A "community of interest" is just a grouping of people with a common interest (usually, a common interest that legislation might benefit). Kansas' 2002 guidelines offered a adequately typical definition: "[s]ocial, cultural, racial, indigenous, and economical interests mutual to the population of the area, which are probable subjects of legislation."

Several of the other principles higher up may be seen equally proxies for recognizing rough communities of involvement. For instance, a requirement to follow canton boundaries may be based on an assumption that citizens inside a county share some common interests relevant to legislative representation. Similarly, a compactness requirement may exist based on a similar assumption that people who live close to each other have shared legislative ends. But each of these proxies may likewise be imperfect: people with common interests don't mostly look to geometric shapes — or fifty-fifty strict political lines — when they consider where they want to live. Considering communities of interest direct is a way to step past the proxy.

Partisan outcomes

Most scholarly and popular attention to redistricting has to do with the partisan upshot of the process, though partisan impacts are hardly the only salient impacts.

The federal constitution puts few practical limits on redistricting bodies. Private districts can be drawn to favor or disfavor candidates of a sure political party, or individual incumbents or challengers (indeed, the Courtroom has explicitly blessed lines fatigued to protect incumbents, and even those drawn for a niggling bit of partisan advantage). As for the district plan as a whole, the Supreme Court has unanimously stated that excessive partisanship in the procedure is unconstitutional, merely the Court has too said that federal courts cannot hear claims of undue partisanship because of an inability to decide how much is "too much."

State law, still, increasingly restricts undue partisanship. In 2010, only 8 states directly regulated partisan outcomes in the redistricting procedure (as opposed to attempting to achieve compromise or balance through the structure of the redistricting body); now, the constitutions or statutes of nineteen states speak to the effect for state legislative districts, and 17 states practice the same for congressional districts.

Most of these country-law provisions prohibit "disproportionately" favoring (or disfavoring) a candidate or party, which might include both intent and outcome; some, similar Florida, specify that the intent to favor or disfavor is impermissible. Ohio'southward law specifies that the state legislative plan, every bit a whole, may not be drawn "primarily" to favor or disfavor a party, and separately specifies that the plan's overal partisan commune alignment should "correspond closely" to statewide partisan preferences. And both Rhode Island and Washington provisions speak in terms of fair and constructive representation, but without much construction by state courts to requite farther pregnant.

Arizona, Colorado, and Washington are the just states that affirmatively encourage districts that are competitive in a general election, in slightly different ways; in each case, this is a goal to be implemented only when doing and then would not detract from other state priorities. New York prohibits discouraging contest, which is slightly dissimilar. And Missouri purports to establish a construction for both rough partisan equity and competition, though its particular implementation of the terms amounts to negligible constraint in practice.

Arizona, California, Iowa, and Idaho ban because an incumbent's home accost when drawing district lines; many of the same states also limit the use of further political data like partisan registration or voting history. Note: where minority populations nowadays the possibility of obligations under the Voting Rights Human activity, those drawing the lines may have to consider partisan voter history to assess racial polarization, no matter what state police provides. Likewise, it is important to remember that every conclusion to draw district lines in ane identify or some other has a political effect; lines drawn without looking at underlying voting data can be simply as politically skewed equally lines fatigued with the information in mind.

Other state rules

There are 3 other notable structural rules that, in some states, govern the location of district lines.

- The first is a "nesting" requirement. In states where districts are "nested," the districts of the land Senate are constructed by combining two or iii country House or Assembly districts (or the districts of the state Firm or Associates are constructed by dividing upward each state Senate district). In contrast, without nesting, the districts of each legislative house are independent; they may follow the same purlieus lines, but they don't have to. In eighteen states, state constabulary asks that the lower and upper legislative firm districts exist nested where possible; of these states, in California, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Utah, the law amounts to crude preference rather than mandate.

- The second rule concerns districts where ii, iii, or more representatives are elected from the same commune; these are called "multi-member" districts. Since 1842, federal law has prohibited multi-member districts for Congress, but many local legislatures even so elect several representatives from a single district. In the state legislature, Arizona, New Jersey, Due south Dakota, and Washington elect all lower firm members from multi-fellow member districts; 9 other states expressly authorize the use of i or more multi-member districts. In some instances, multi-member districts may be used together with nesting rules; in Arizona, for case, each district elects 1 state senator and two state representatives. In other cases (like West Virginia), multi-member districts for i legislative bedroom are not tied to the districts of the other bedroom: a Senate district and a multi-member Assembly commune are entirely unrelated. Multi-member districts in which each representative is elected by majority vote may raise concerns under the Voting Rights Act, though such concerns can be alleviated through some alternative voting rules.

- The tertiary rule of notation is the "floterial" district: a district that wholly or partially overlaps other districts in the same legislative sleeping accommodation. Florida, Mississippi, and New Hampshire expressly permit floterial districts. Nigh floterial districts arose as a style to preserve political boundaries while also limiting severe population disparities. Imagine a state where the average district's population is 100, but there are two adjacent towns with 150 people each. One way to ensure equal population is to carve up upwardly the towns so that there are 3 mutually exclusive districts with 100 people each. An alternative is to create i district serving each boondocks, and ane "floterial commune" elected by the 300 people in both towns together, so that the 300 people accept the same 3 total representatives.

What Is The Most Congressional Districts Can Differ In Size,

Source: https://redistricting.lls.edu/redistricting-101/where-are-the-lines-drawn/

Posted by: nicholscappereen.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Most Congressional Districts Can Differ In Size"

Post a Comment